Nickel Déjà vu: Land Grabbing Smears China-backed Quartz Downstreaming Project

Kadir walks at his neighborhood backyard at Sembulang village, Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 27, 2023.

Kadir walks at his neighborhood backyard at Sembulang village, Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 27, 2023.

On a tranquil afternoon in the fishermen's village of Sembulang, Rempang Island, Kadir gazed at his seaside abode. He looked contemplative. At 69 years old, Kadir never expected an imminent eviction from this village.

Kadir is a fisherman who has lived in Sembulang for more than four decades. He has a wife and two children. Every morning, he would go out to the sea and bring back Spinefoot fish, yellow tail fish, shrimp, or squid. That is a life of peace that Kadir would never give up.

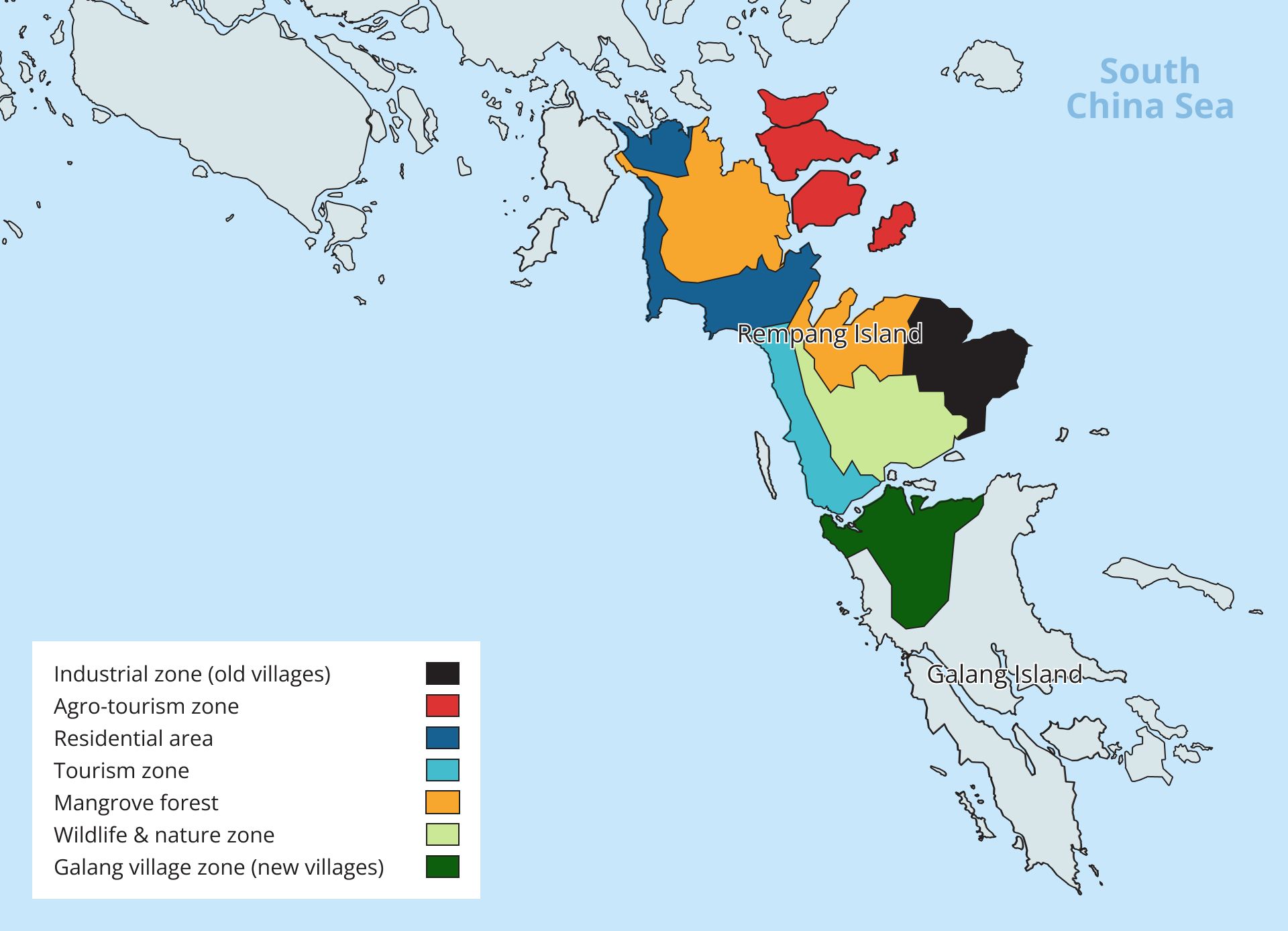

But now, Kadir’s family and hundreds of others might be forced to leave. His village, along with 15 more in Rempang, will be transformed into an eco-city and an industrial zone. This mega project will also see the construction of a $11.6 billion glass and solar panel factory by China’s Xinyi Group, which has been touted as the second-largest of its kind in the world.

This is not the first time that a major green project is forcing out local communities. Indonesia’s nickel smelters development, which is also backed by China, has been associated with displacement and land-grabbing.

The island of Rempang is strategic because its surrounding islands are rich in quartz and silica sand, the raw materials for solar panels and microchips in electronics. According to an internal document from Batam Indonesia Free Zone Authority (BP Batam) obtained by CGSP, over 70% of the entire Sembulang district, or nearly 85 hectares, is earmarked for an industrial zone. This area will house a logistics port and warehousing facilities.

Local government officials have boasted that the plan will bring prosperity to the region. But Kadir, the fisherman, disagreed.

It’s not that he opposes development, Kadir explained. He was just hoping that the investment would not have to affect the villagers’ lives.

Kadir and his family choose to stay in his home at Sembulang village, Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 27, 2023.

Kadir and his family choose to stay in his home at Sembulang village, Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 27, 2023.

***

The Rempang Eco-City initiative emerged nearly 20 years ago. In 2004, an agreement was sealed between the Batam City Government and Makmur Elok Graha (MEG), a subsidiary company of Artha Graha, a conglomerate group owned by one of Indonesia’s richest businessmen, Tomy Winata.

With a total development area covering over 7,500 hectares, the project aims to attract an investment of $24 billion by 2080. Fast forward to July 2023, in Chengdu, China, MEG signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Xinyi to build the glass and solar panel factory inside the eco-city complex. Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo witnessed the signing ceremony.

The Eco-City Project Zone's plan. Source: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute (Map created by Neo Hui Yun Rebecca). Illustration by Alex Santafe

The Eco-City Project Zone's plan. Source: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute (Map created by Neo Hui Yun Rebecca). Illustration by Alex Santafe

The government said that Xinyi’s investment is expected to “absorb a workforce of about 35,000 people, mainly in the downstream quartz and silica sand processing in Rempang.” A month later, the project was included in the list of National Strategic Projects by the Minister of Economic Affairs. This means that the project will be eligible for special facilities from the government, and is prioritized for completion.

The MoU with Xinyi holds a high significance in the global shift toward environmentally friendly energy, as the facility is hoped to be a key player in supplying solar panels worldwide. The Rempang project is also poised to intersect with the unfolding “de-risking” trade policy involving China, the United States, and the European Union. As of 2022, China accounted for three-quarters of the world's solar panel production and 97% of the silicon wafers within the panels.

Muhammad Rudi is the head of local authority body BP Batam. In an exclusive interview with CGSP, Rudi talked about how he was given the task to free up the land. This is Rudi’s top priority. After that, he can hand the land over to MEG, which will work with Xinyi for development.

The chairman of BP Batam Batam, Muhammad Rudi held a meeting inside BP Batam building in Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 27, 2023.

The chairman of BP Batam Batam, Muhammad Rudi held a meeting inside BP Batam building in Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 27, 2023.

There are about 960 families who reside in the 2,000 hectare area where the first phase of the project will be built. Composed and serious, Rudi complained about not being given enough time to do his job.

“The time given is not enough to convince [the families to relocate] and to prepare proper regulations about compensation,” Rudi said.

At the moment, the government is offering to relocate the residents affected. Each family is promised a house worth IDR 120 million ($7,600) on a 500-square meter plot of land. They will also receive about IDR 1 million in living expenses per person for each family.

The villagers are not happy with the relocation plan for many reasons. The land has been in their possession for generations, and they feel that the compensation offered isn’t enough. And so, the villagers are putting up a fight.

Rempang's unrest on September 7, 2023. Video provided by a resident.

Rempang's unrest on September 7, 2023. Video provided by a resident.

On the morning of September 7, Ahmad – who is using a pseudonym for fear of retaliation from the local authorities – joined hundreds of others from four neighboring villages to stop an Indonesian task force from taking over their land. They were up against the military, the policy, and Batam security officers.

The police dispersed the crowd using tear gas. Ahmad tried to run away. "In the evening, I was arrested by the police,” Ahmad told CGSP. The police arrested a total of 43 villagers who protested that day, local media reported.

Rempang's unrest on September 7, 2023. Video provided by a resident.

Rempang's unrest on September 7, 2023. Video provided by a resident.

Residents believed they can be evicted any moment now. Since the protest, the Rempang community has guarded every village entrance, including intersections that lead to their villages.

Jannus TH Siahaan, a researcher with The Indonesian Initiative for Sustainable Mining (IISM), said that the government should have worked to involve the local communities during the planning stage. This is to ensure that any relocation would be done with empathy and a deep regard for local historical and cultural heritage.

“It is crucial to acknowledge that the initial approach [by the Indonesian government] was misguided, Siahaan noted.

He believed that adopting a more community-centered persuasion strategy is essential. Authorities could have allowed more time for people to grasp the urgency and benefits of the proposed changes.

“Since it directly impacts the lives and sustenance of the local populace, their values and traditions must be honored for companies and governments to earn respect within the community,” Siahaan said.

***

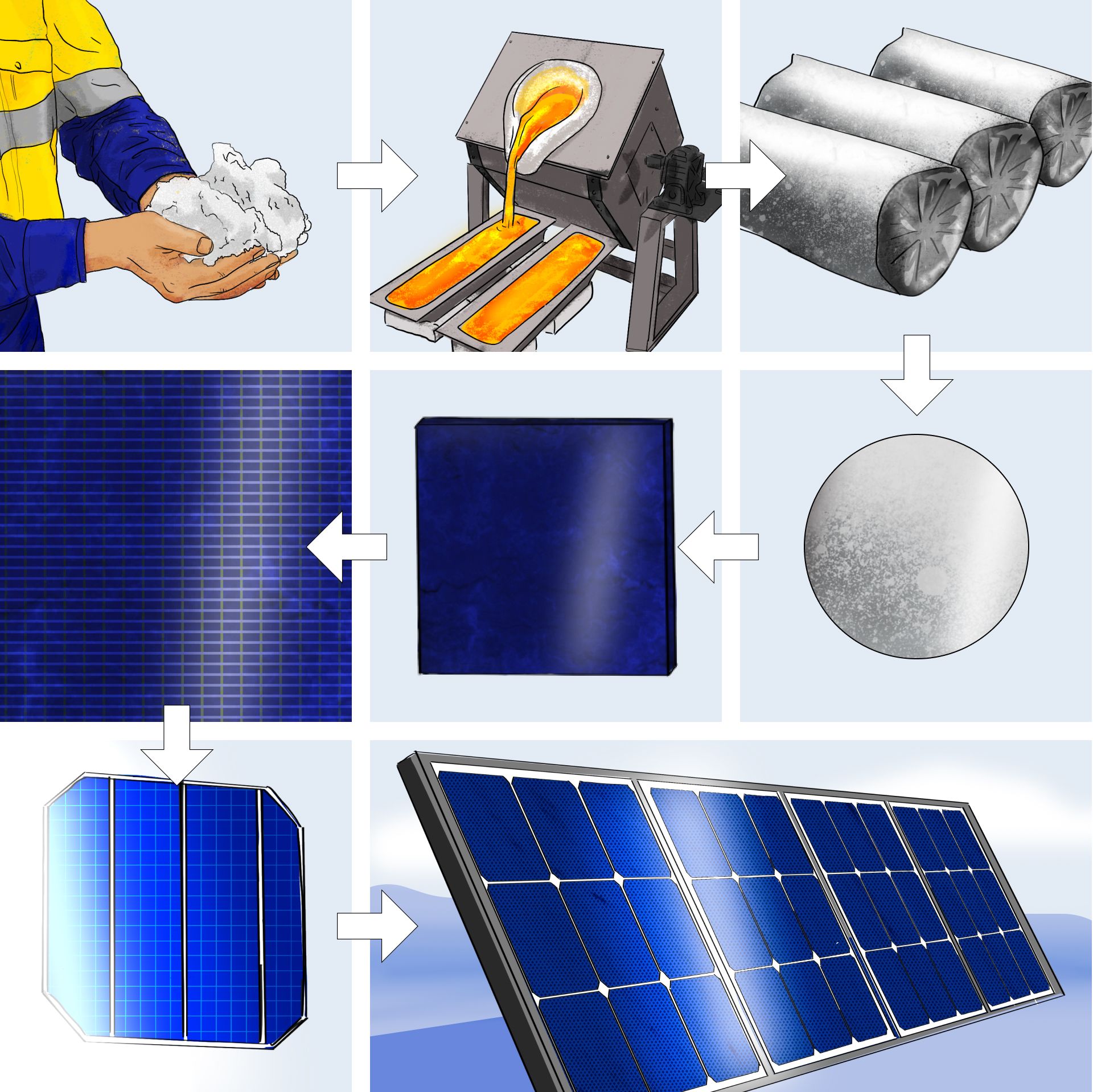

How to turn quartz sand into a solar panel. Illustration by Alex Santafe.

How to turn quartz sand into a solar panel. Illustration by Alex Santafe.

Quartz sand that contains silicon dioxide is the most suitable for solar panel production. The sand is first heated at high temperatures to separate the silicon and oxygen components.

The metallurgical-grade silicon then undergoes a purification to turn it into semi-crystalline silicon, which will be mixed with boron to create ingot blocks before slicing them into silicon wafers.

Next, the silicon wafer will be treated with phosphorus, transforming it into a solar cell capable of generating electricity.

Quartz and silica sand play a crucial role not only in solar panels, but also in the production of microchips. Natuna and Lingga, the islands surrounding Rempang, are rich with this commodity.

Illustration by Alex Santafe.

Illustration by Alex Santafe.

Ady Indra Pawennari, the chairman of the Indonesian Quartz Miners Association (HIPKI), hopes that Indonesia can play a vital role in supplying quartz sand for Xinyi. At competitive purchase prices, hopefully, he added.

Pawennari said that several companies have expressed interest in purchasing quartz sand from HIPKI members. But, “we have not received any definitive proposal from Xinyi,” he said.

***

In Pictures

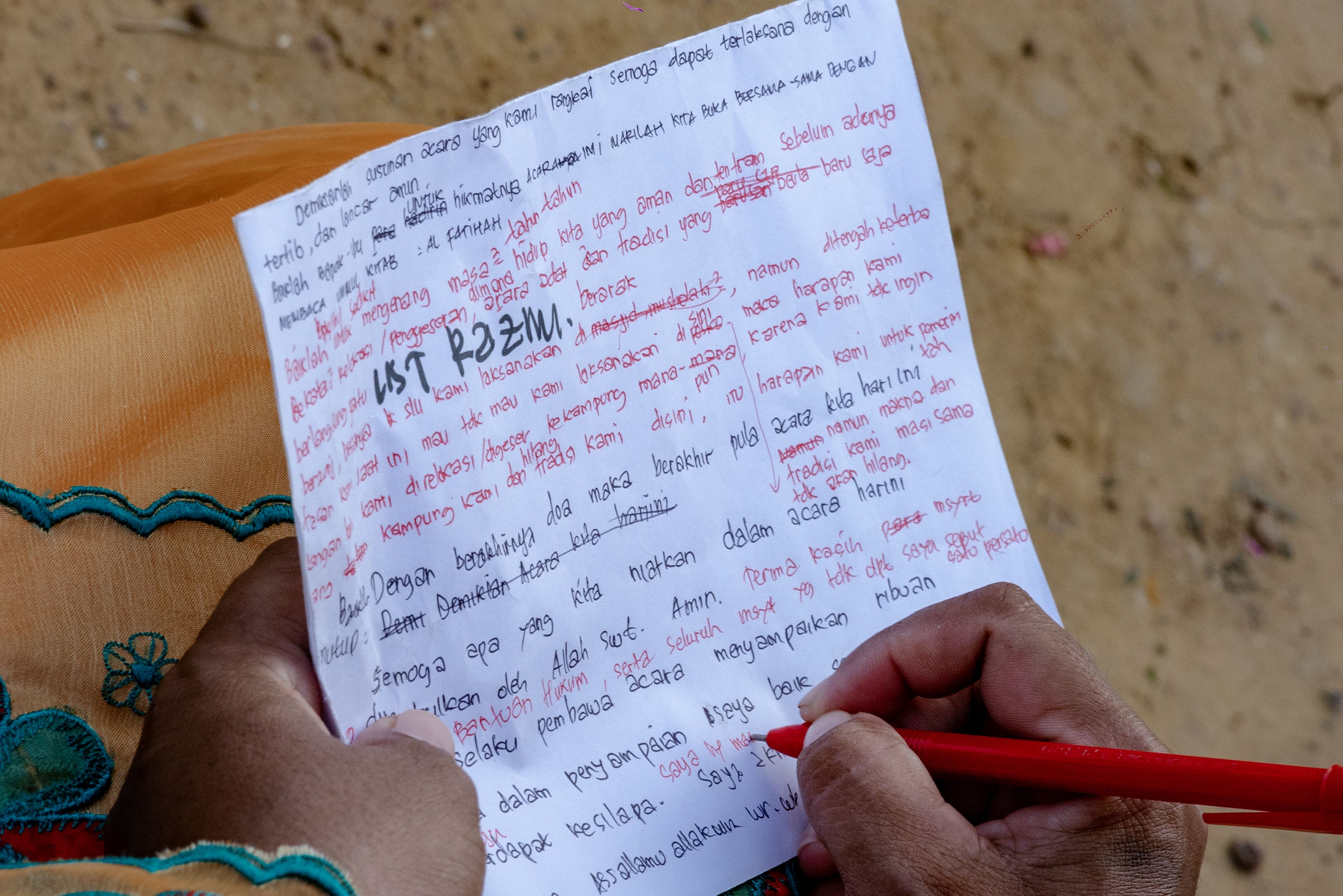

When CGSP's team visited Rempang at the end of September, 2023, residents were still grappling with the aftermath of the unrest. Resistance against the project and their eviction from the island, persisted.

A man rides his bike at Pasir Panjang village in Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

A man rides his bike at Pasir Panjang village in Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

A protest text is seen during Mawlid Al-Nabi commemoration at Pasir Panjang village, in Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

A protest text is seen during Mawlid Al-Nabi commemoration at Pasir Panjang village, in Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

A family visit a their relation who was arrested while Sept 11 protest at Batam police office in Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

A family visit a their relation who was arrested while Sept 11 protest at Batam police office in Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

Pasir Panjang residents held a protest in their village during Mawlid Al Nabi in Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

Pasir Panjang residents held a protest in their village during Mawlid Al Nabi in Rempang, Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

A family visit a their relation who was arrested while Sept 11 protest at Batam police office in Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

A family visit a their relation who was arrested while Sept 11 protest at Batam police office in Batam, Riau Islands, Indonesia on September 28, 2023.

Rempang was supposed to be empty at the end of September, but the residents’ protest successfully delayed that due date. The government appears to be reevaluating its tactics, including working to raise the compensation package.

Beyond housing, the government plans to facilitate the installation of water pipes, electricity, roads, and telecommunications, as well as fishing docks and fishing equipment to persuade Rempang fishermen to relocate. BP Batam estimated the construction cost of relocation housing to reach IDR 1.8 trillion, with the development anticipated to span over two years.

But many families like Kadir’s – the fisherman from Sembulang village – are adamant to stay, no matter what happens. "I do not wish to accept any form of payment from the Chinese company,” Kadir said. “It does not sit right with me.”

***